By Draven Copeland, Editor-in-Chief

As soon as the theater house opened for the Fall 2024 performance of Antigone on Pellissippi State’s Hardin Valley campus, the waiting audience anxiously funneled together as a stage manager led the way through a dark, narrow hallway.

As the group slowly huddled together towards the house, I had many questions. Was this crowd of maybe 30 people going to make up the entirety of the sold out seating? Why didn’t the house open until just 15 minutes before the show’s start time? Why lead us so slowly through the dark? All of these questions were answered when the destination was finally reached through the black curtain at the end of the hall: we were to take our place on the stage.

“What a piece of work is man!”

Sophocles, “Antigone”

The 495 open seats of the Clayton Performing Arts Center’s auditorium, which remained vacant for the entirety of the show, were neglected in favor of three stands of seating surrounding a small lifted stage in the center of the larger one. The performative nature of the journey to the relatively minimal seating erased all thoughts of a passive role as an audience member, thrusting the crowd into the same light as the performers.

The only space left onstage for the performers was a circular stage-upon-a-stage designed as a giant clock; not only was this “black box” formation a way of bringing the audience quite literally inches from the action, but of bringing an added layer of poignancy to the events performed as well.

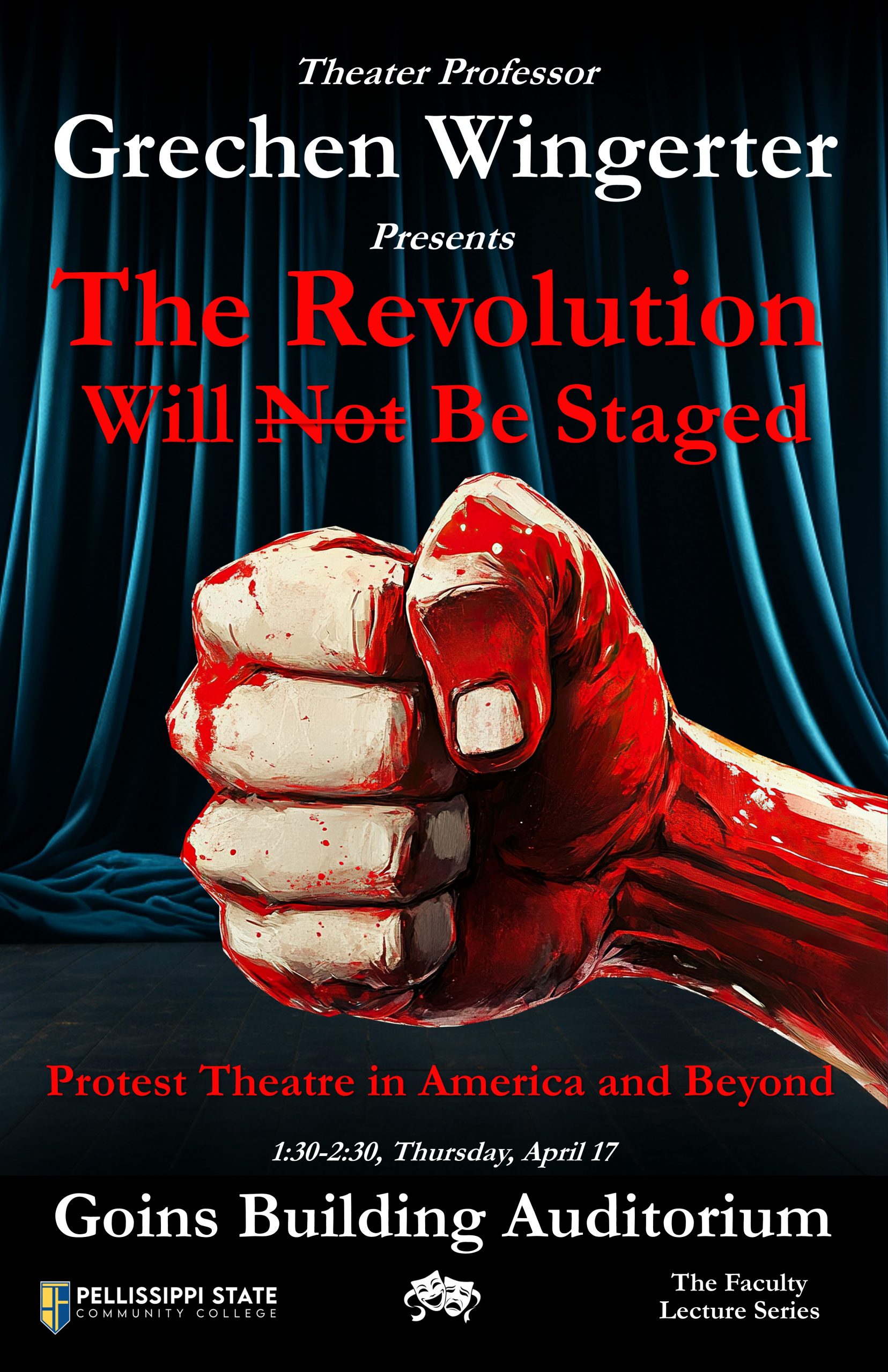

The third and final of Sophocles’ “Theban plays,” Antigone concerns the life and death of the titular daughter of Oedipus, chronicling her moral conflict with the reigning King Creon when her honorary burial of her brother, Polynices, is discovered by the royal guard. All hands both onstage and behind the scenes brought this timeless story not only to life but to emotional resonance with the crowd, due in large part to Director Grechen Lynne Wingerter’s stark vision to expertly balance modernity and traditionalism being brought to life from the fundamental blocking of the action to the costume color choices for the main players.

Amber Williams’ costume design combined modernity with classical Greek mentality, incorporating a red-vs-blue political battle (of which all but the female main characters’ costumes conform to) into an age-old tale of money and power against love and acceptance.

The minimalist scenic design/technical direction by Claude Hardy further promoted the audience’s personal interpretation of the events, foregoing any clear geographic or period placement beyond a screen which would at times display Greek ruins, keeping the introspective repetition of the clock on which the action took place the centerpiece of the composition.

Onstage, the opposing lead roles of Antigone and Creon were masterworks by McKenzie Dawson and Nehemiah Davis respectively. Dawson’s tear-wrenching final cries for her character’s life were well-earned as she was able to finely construct her character’s emotional arc throughout the play in just the few scenes she had. Davis’ unwaveringly brutal performance was incredibly strong, made even stronger when it was realistically shattered by tragedy all too late. Not only did these performances complement one another emotionally, but narratively as well: Davis’ expertise in crafting such a faithful representation of ignorance and hunger for power gave context to Antigone’s righteous rebellion, while Dawson’s tearful and deeply emotional performance enhanced the clarity of Creon’s unsympathetic heartlessness.

Chorus performances, led by the mysterious Francesca Reggio, provided needed context between the two leads’ major scenes with ritualistic choreography that often surrounded the audience’s seating. While these scenes were all very intriguing on their own, their stylish use of mysticism and masked actors culminated perfectly into understudy Micheala McDonald’s appearance as Teiresias, the blind prophet whose influence finally breaks Creon’s infallible spirit (originally performed by William Painter in this production).

The beauty of a well-constructed production is the effortlessness it has in creating a truly unique experience for the audience, and Wingerter’s production of Sophocles’ Antigone succeeded in that respect at all levels. With a 1,500 year old text such as this one, the easiest route to an inaccessible and dense production was avoided in favor of one that is emotionally resonant and especially poignant even to this day. Not only would this show please long-time theatre enthusiasts, but its overall quality may well inspire the casual theater-goer to look out for more productions at Pellissippi State Community College.