By Charlie Dobyns, Science Writer

Picture the forests of the American southeast. See the greenery. Hear the songs of cardinals and Chickadees calling to their mates. Feel the cool air coming off the streams. The landscape is incredible, but a crucial piece is missing. For at least 10,000 years red wolves roamed the American southeast, acting as the area’s apex predator and balancing the ecosystem. Today just around 20 remain in the wild.

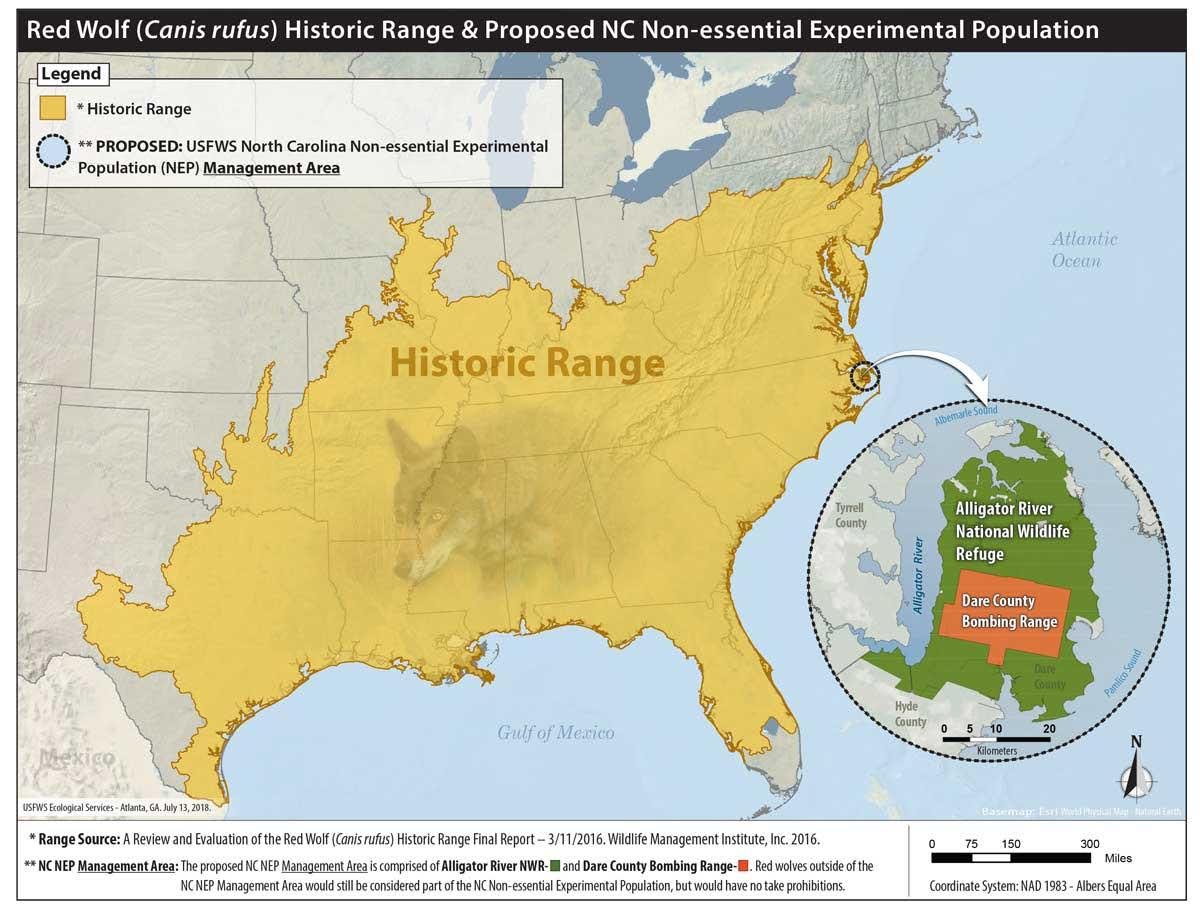

The native range of the Red Wolf has been decimated. While the species once spanned from Texas to New York, the entire current wild population resides on 237.5 square miles of the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge in North Carolina.

The Southeastern United States is currently undergoing a dramatic and potentially catastrophic process of trophic cascade, which refers to an ecological phenomenon caused by the removal of apex predators in an ecosystem, resulting in the downward spiral of all life dependent on the ecosystem’s balance.

Trophic cascade eventually leads to the death of an ecosystem, where life in a given area is no longer sustainable. A similar process was allowed to happen after the removal of gray wolves from the Yellowstone region, but with wolf reintroduction efforts the ecosystem is on a path to recovery.

Red wolves are the endemic apex predator of the southeastern United States but have been functionally removed; it is imperative to reintroduce them to the southeastern United States in order to halt the process of trophic cascade and to allow the ecosystem to recover.

In well-balanced ecosystems apex predators like the red wolf are responsible for the maintenance of everything else below them; they eat mesopredators (foxes, coyotes, feral cats, and the like) and large prey items, while the mesopredators eat small prey items. Taking large predators out of the equation allows mesopredators to flourish but grants the same ability to large prey animals such as deer, causing further imbalance to an ecosystem. This imbalance is often referred to as mesopredator release.

An example of mesopredator release comes from a study on native species in the Lago islands was conducted by John Terbough in 1993 after manmade infrastructure granted olive capuchin monkeys access to the islands. The capuchin monkeys, while considered a mesopredator in their native ecosystem, had no known predators on these islands, and the islands’ native species had not previously experienced a predator of this level. Conducted surveys revealed that one hundred percent of native birds’ nests had been raided, native howler monkeys were out-competed and began to starve to death, and even the trees modified themselves to become sharper, bitter, and poisonous in an adaptive response to the fierce overgrazing. Eventually, once the land had been stripped of its natural resources, even the invasive capuchin monkeys began to die off.

This study exemplifies what can happen to an area when mesopredators are allowed to flourish without interruption from a more powerful apex predator, and the same study has been repeated countless times in countless ecosystems that are all falling victim to trophic cascade. These studies all end in the same result: native species die off en masse, and the invaded lands become uninhabitable.

The Southeastern United States is already seeing the effects of mesopredator release. The vacuum left by the disappearance of red wolves has allowed for an overabundance of mid-level predators like coyotes, foxes, and feral cats, who are now hunting small prey animals at unnaturally high rates, eventually driving them to extinction.

According to The Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services “free-ranging domestic cats kill 1.3-4.0 billion birds and 6.3-22.3 billion mammals annually.” While humans often see feral cats’ destructive abilities similarly to the way they would see their own docile house-cat, the fact remains that they are an invasive species and an ecological threat that humans don’t currently have the infrastructure to neutralize. Red wolves, however, can help. The feral cat is an easy prey item for red wolves, and a problem that can be quickly solved by their reintroduction, as the domesticated pet, abandoned and left to fend for itself, is now causing ecological wreckage on an unimaginable scale in a desperate bid for its own survival.

The Southeastern United States is also struggling to maintain botanical biodiversity due to an overabundance of white-tailed deer, who currently are without a predator to maintain their population. The deer in the American Southeast are being allowed to overgraze native plant species into extinction, paving the way for a dangerous monoculture. Surveys done in West Virginia by Nicole Elmer on the native orchid species called the Showy Lady’s Slipper, concluded “At one site, deer removed major portions from 65-95% of the stems in a 3-year episode.”

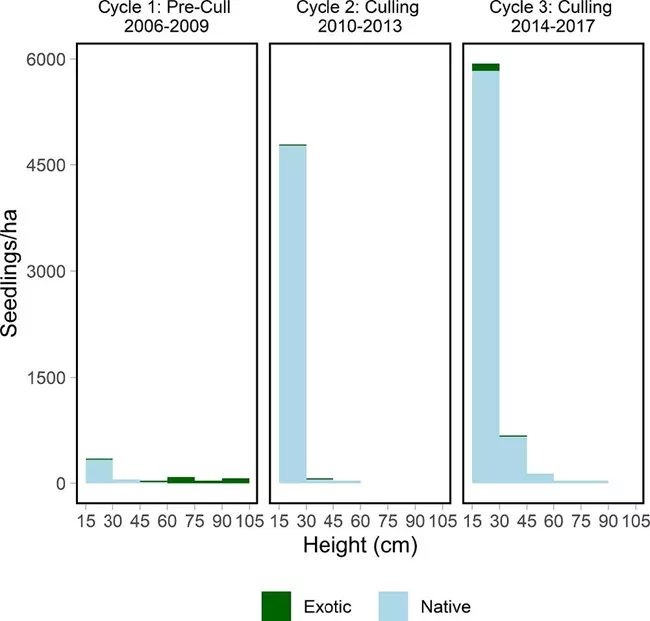

The devastation of native plant populations makes space for already invasive species to greaten their spread. For example, Japanese stilt grass arrived in America in the 1960s and, as a browse-tolerant and deer-avoidant species, it was ignored by the white-tail, who instead chose to browse on potentially competitive native species , allowing stilt-grass to become a monoculture abundant in all the American Southeast. Biologists with the National Parks Service surveying stilt-grass abundance in post deer cull environments noticed major improvements in population numbers of native species, explaining “Stiltgrass often requires some kind of disturbance, such as that caused by deer, to persist in an area.” As a monoculture of stiltgrass flourishes because of white-tail avoidance, life will soon start to fade as native species that depend on having available variety will slowly starve to death and face extinction.

A haunting reminder of what can happen when a monoculture prevails is the Kaibab mule deer, whose fate was detailed in William Stoltzenburg’s novel Where the Wild Things Are. In 1906, deer hunting was banned on the Kaibab plateau, and any potential predators were killed off to protect the deer populations. These efforts were successful as, according to Stoltzenburg, “over the next 25 years populations jumped from four thousand to 100 thousand.” The success of the mule deer ended abruptly in the winter of 1924 when, after grazing the plateau barren, eighty thousand deer died of starvation. As deer populations rise, they edge closer to their fall.

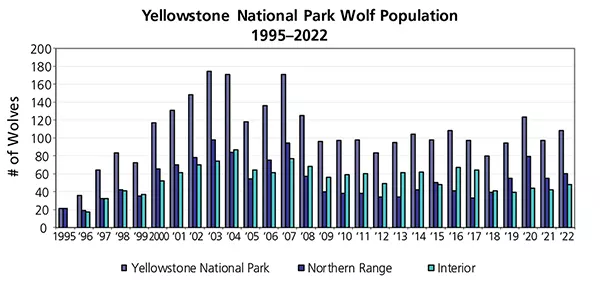

Evidence of the success of large predator reintroduction in the American Southeast can be found in the history of Yellowstone National Park. In 1926, the last wolf pack was killed after a bounty had been put on the heads of wolves by the U.S. government. In the following years, the park’s ecosystem fell victim to a trophic cascade similar to the one currently being experienced in the American Southeast; large numbers of native Aspen trees died off due to overgrazing by elk. Coyote numbers then increased, causing a dramatic decrease in small prey species.

From 1994-1995, thirty-one wolves were brought to the park, acclimated, and released, as stated by the National Parks Service. A survey conducted in January of 2023 by the National Parks Association shows that “there are at least 108 wolves in the park” and numbers are on an upward trend.

In the 1970’s, the last red wolf populations in the United States were taken into captivity for protection and breeding purposes, as the species was declared extinct in the wild. A progress report from the United States Fish and Wildlife Services (USFWS) on red wolves states that “On November 12, 1986, four pairs of adult red wolves arrived at Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge (ARNWR)” as part of an experimental population. Unfortunately, although the ARNWR release occurred before the Yellowstone release, according to USFWS, the red wolf population in the wild is now estimated at only 21 individuals.

The reintroduction in ARNWR has not been considered successful, with high rates of mortality primarily caused by bullet woundsWhat is needed for large predator reintroduction to be successful is the proper protection of reintroduced individuals, as well as a greater number of resources allocated to the wellbeing of the species.

As red wolves have become endangered because of human interference, the responsibility to fix the problem rests solely on human heads. Red wolves are endemic to the eastern-southeastern United States, meaning that when colonizers first reached the shores of America, the red wolf was the first large predator settlers encountered and subsequently killed. The Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) acknowledges the cause of red wolf endangerment as “hunting, human encroachment on their habitats… and loss of prey due to overhunting and urbanization,” all of which is based in human interference.

With only about 21 wolves left in the wild, their time is running out. The AZA is working tirelessly to keep the species alive, but the burden of species survival cannot rest on one organization. Humans have had a detrimental impact on the world’s ecology as whole, and we have the capability to fix it before trophic cascade comes crashing down. If we do nothing, studies have shown time and again that the land will become barren, there will be nothing left to hunt or harvest, and we will be to blame.

There are some reasons why humans may not want to reintroduce red wolves to the ecosystem, however. Everyone has grown up hearing stories of big bad wolves, training people to fear the looming creature with sharp teeth and a hunger for flesh. People fear the dangers associated with wolves: the loss of pets, livestock, potential hunts, and personal loss of life. It is true that wolves have been known to attack and kill humans; however, a report by the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research confirms that in North America between the years 2002-2020 “there have been [only] two documented fatal attacks.”

While a bias could be present because North America has a relatively low wolf population, the same survey conducted in the region of Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and Moldova, areas where wolf populations are much higher and rabies is prevalent, revealed “16 cases of attacks… all victims survived.” Realistically, the chances of being killed by a wolf are almost nonexistent.

Another point of contention for wolf restoration comes from farmers and hunters, as they fear that wolves will harm livestock and interrupt herd patterns. However, a study by Washington State University showed that when wolf deaths increased in a given year, the following year would show an increase of wolf-related livestock deaths. While we don’t yet fully understand why this occurs, the study does suggest that with a healthy wolf population, livestock deaths decrease. That said, wolves are not the only culprit in livestock killings. Mesopredators like coyotes and foxes are also responsible for large numbers of livestock deaths, and a healthy population of wolves can help prevent such killings by culling mesopredators.

It is important to note that all statistics on wolf attacks are based on gray wolf behavior, as there are no studies available to suggest rates of red wolf attacks due to the low population. Red wolves have been found to be much less aggressive and much more timid than gray wolves, suggesting that, if they were to be reintroduced, attacks and animal death rates would be far fewer.

Large predator reintroduction initially sounds like a fringe solution, but it is possibly the only action that can save the entire Southeastern ecosystem. There are far too many possible consequences for this to be allowed to continue without intervention. The red wolves need human assistance, and the ecosystem needs red wolf assistance. The extirpation of red wolves was a tragedy, but it doesn’t have to be the end of their story. By reintroducing red wolves to the American southeast, a change can happen to allow the survival of all the species present in that region.